Over the past few weeks, sentiment toward Australia’s housing market has shifted markedly to the upside as headwinds to stronger credit growth have either eased or been removed entirely.

Recent monetary and regulatory developments are positive for the outlook of Australia’s housing market and Residential Mortgage Backed Securities (RMBS) and mildly positive for commercial banks, but won’t offer much upside for property developers in the near term.

We believe property prices should find a floor in the second half of calendar 2019 (2H19) as sentiment improves and headwinds are removed.

Property prices should find a floor in 2H19 as sentiment improves and headwinds are removed.

Over the past few weeks, sentiment toward Australia’s housing market has shifted markedly to the upside. The reappointment of the Coalition government laid to rest uncertainty over tax changes affecting the property sector that had been proposed and long-foreshadowed by the opposition Labour party.

Although it had all the indications of ‘policy on the run’, we presume the Coalition government also intends to proceed with its policy to effectively underwrite the deposit requirement for first home buyers.

Shortly thereafter, the prudential regulator for Australia’s banking system, the Australian Prudential Regulation Authority (APRA), announced a proposal to in-effect increase the borrowing capacity of households (by lowering serviceability requirements), particularly as interest rates appear set to fall further in the near term and remain lower for longer.

On the same day, the Reserve Bank of Australia (RBA), as convincingly as it could without admitting as such, indicated that the next move in interest rates would likely be down. Markets had fully priced in a 25bps cut, so it came as little surprise when the RBA followed through and lowered the official cash rate by 25bps to 1.25% on 4 June 2019, and then again by a further 25bps at its July meeting.

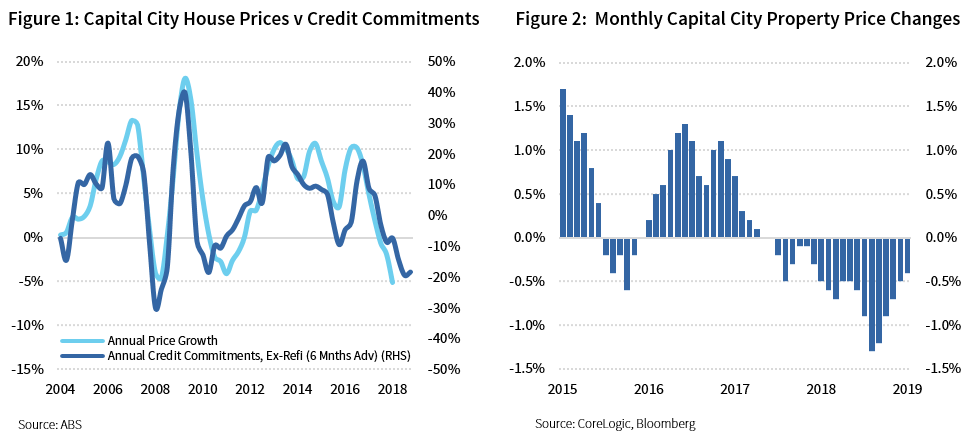

As we have discussed prior, a strong relationship exists between credit and property price growth (see Figure 1). This makes sense as overwhelmingly, prospective buyers require some form of financing to purchase a property.

For the last two years, following a sustained increase in property prices between 2012 and 2017, price growth has slowed and indeed turned negative as credit supply became constrained and policy uncertainty weighed on borrower intentions, particularly for investors (see Figure 1 and 2).

With policy uncertainty now removed (anecdotally, banks are suggesting demand for borrowing has increased markedly following the election outcome), and supplemented by falling interest rates and lower serviceability requirements, we believe property prices should find a floor in the second half of calendar 2019 (relatedly, we believe first home owners assistance is unlikely to have much influence on property prices).

APRA changes to increase borrowing capacity by up to 15%

APRA changes to increase borrowing capacity by up to 15%On 21 May 2019, APRA announced a proposal to remove the interest rate floor of 7.0% when banks assess the ability of borrowers to service their loans. Banks would still be required to apply a buffer of at least 2.5% above the loan interest rate. APRA noted two primary reasons for the proposal:

- the low interest rate environment is now expected to persist for longer than originally envisaged (back in 2014 when the floor was introduced). This may mean that the gap between actual rates paid and the floor rate may become unnecessarily wide; and

- compared to 2014, when a single standard variable rate was used as the basis to price all mortgage loans, authorised deposit-taking institutions (ADIs) have introduced differential pricing for mortgage products. The merits of a single floor rate are therefore less obvious, particularly as it will be most binding on owner-occupiers with principal and interest loans, and least binding on investors with interest-only loans.

We would also add, in our opinion, that the changes from APRA also relieve some pressure on the commercial banks to pass-on in full any further interest rate cuts (see further below for our rationale). Unsurprisingly, the greatest increase to borrowing capacity is afforded to owner-occupiers (and to a lesser extent, investors) on principal and interest-terms, with increased capacity for households on interest-only terms around 5% p.a. (see Figure 3).

Many households are unlikely to avail themselves of the maximum amount of increased borrowing capacity, as the table above assumes the lowest possible rate on offer is applied, which generally assumes the lowest risk settings (for example, a loan-to-valuation of less than 80%, and generally only available to borrowers who take up a package option).

Nevertheless, the proposed changes to serviceability are highly likely to increase the borrowing capacity of many new borrowers, particularly if interest rates fall further.

Credit conditions to remain tight, while banks are unlikely to universally pass on future rate cuts in full

Despite the high likelihood of lower serviceability floors, we believe overall credit conditions will retain a tightened bias. One of the primary issues highlighted by the Royal Commission was the banks’ reliance on the Household Expenditure Measure (HEM) to measure a borrower’s household expenditure.

The HEM is produced by The Melbourne Institute and represents ‘a measure that reflects a modest level of weekly household expenditure for various types of families’. While we note that banks in general adopt the higher of declared expenses or the HEM, the Interim Report found that in a targeted review conducted by the banking prudential regulator in 2016/2017:

‘…in as many as three out of every four home loans…the banks assumed that the borrower’s household expenditures were equal to the relevant HEM. … Using HEM as the default measure of household expenditure assumes, often wrongly, that the household does not spend more on discretionary basics than allowed in HEM and does not spend anything on ‘non-basics. … It follows that using HEM as the default measure of household expenditure does not constitute any verification of a borrower’s expenditure.’

While banks generally adopt the higher of declared expenses or the HEM, the shortfall of this approach is the apparent lack of expense verification. The household expenditure estimate includes a prospective borrower’s lifestyle across four categories: ‘student’, ‘basic’, ‘moderate’, and ‘lavish’. According to UBS (April 2018), "in the vast majority of cases the 'basic' lifestyle assumption is used". We estimate that if a ‘moderate’ or ‘lavish’ lifestyle is applied, the borrowing capacity reduces by up to 25% and 40%, respectively. The significance of this is currently being tested in the courts in ASIC (the corporate regulator) v Westpac.

Reliance on the HEM has reduced, while there are many anecdotal suggestions from market participants that the heightened focus on expense verification is restricting the flow of credit and reducing household borrowing capacity. So while a lower serviceability hurdle is likely to assist new borrowers to a varying degree, we believe the renewed focus on expense verification will neutralise much of the increase in borrower capacity from APRA’s proposed changes in the near term, particularly against the backdrop of ASIC v Westpac.

The easing in serviceability also assists the flow of credit while taking pressure off commercial banks to pass on cuts to the official cash rate in full, which comes at the expense of margins. All else being equal, a lower interest rate environment is a negative for bank margins. We estimate around 40% of bank funding is currently paying little or no interest (excluding capital); the ability of the banks to reprice low-rate deposits to offset lower mortgage yields diminishes as interest rates fall.

For variable rate home loans (which make up around 80% of loans outstanding), the primary components of a banks funding costs (which comprise the cash rate, long-term funding costs and basis risk cost) have been falling in recent months (see Figure 4 for falls in basis risk cost changes).

While changes in the cash rate are immediate, changes in long-term funding and basis risk costs take affect over a longer timeframe (for example, changes in the 3-Month Bank Bill Swap Rate [BBSW], which is the benchmark for long-term funding costs, generally take 3-6 months to flow through to profit and loss).

At the same time, banks have increasingly priced their mortgages on a discriminate basis across four main types of loans, across two dimensions: whether the borrower is an owner-occupier or investor, and whether the loan payments are principal-and-interest (P&I) or interest-only (IO) (see Figure 5).

This approach to pricing loans also recognises the fact that banks will be increasingly required to allocate capital based on the risk characteristics of the underlying loan; the riskier the loan, the higher the capital allocation. This explains in part why rates on IO investor loans are roughly 85bps higher than a P&I owner-occupier loan.

As such, with the official cash rate more likely than not to fall in the near term, we believe changes to mortgage rates are unlikely to shift universally and in unanimity with further falls in the cash rate, particularly in the context of a diminishing ability of banks to reprice an increasing proportion of their liabilities.

Why do house prices matter?

House prices also feed into the value of housing assets, with household dwellings accounting for close to 70% of net household wealth in Australia; rightly or wrongly (for another time), the wealth of Australian households is inextricably linked to the value of our houses.

As can be seen in Figure 6, there is a reasonably sound (inverse) relationship between household wealth and savings rates (excluding the Global Financial Crisis between 2008 and 2010); as house prices rise, savings fall (and vice versa). Household savings fell to a ten-year low in late-2018.

While sustained property appreciation between late-2012 through to early-2018 is likely to have influenced this trend, a willingness to sustain consumer spending (see Figure 7), coupled with a lack of meaningful wage growth, has also likely contributed to the draining of household savings more recently (and exacerbated the lag), in our view.

If household savings are to follow this relationship and trend higher in the near term (which is not such a bad development, in isolation), and in the absence of any credible policy reform in the near term to meaningfully increase wage growth (beyond simply relying on easing monetary conditions), consumer spending is likely to fall.

Consumer spending accounts for close to 60% of nominal GDP, and as such, is a significant contribution to economic growth (and employment).

Households’ willingness to spend, particularly on discretionary items, is also influenced by property prices (the oft-referred to ‘wealth effect’) (see Figure 7). More specifically, an increase in spending on household goods is similarly influenced by housing turnover, as households purchase fixtures, fittings etc., to accompany their new purchase.

Outlook for RMBS strengthens, less-so for commercial banks, but no short-term turnaround for property developers

RMBS is a clear beneficiary from the recent developments, in our opinion. We have remained comfortable with RMBS even during the period of recent house price declines, particularly given a preceding period of strong growth (in property prices). While 2018 vintages exhibited a higher proportion of investor and interest-only, a function of increased non-bank issuance, in particular, the weighted-average loan-to-value (LTV) is broadly consistent with all vintages (see Figure 8 and 9).

Stabilising house prices will stem the recent increase in LTV ratios. Falling interest rates and lower serviceability hurdles should support higher refinance rates, notwithstanding our expectation that overall credit conditions will remain tight. Higher refinance rates should result in an increase in prepayment rates, which have fallen noticeably more recently in response to tight credit conditions and lower transaction volumes (see Figure 10).

Prime arrears have been increasing since mid-2017 (around the same time credit conditions began to tighten), although they remain low in an absolute and relative sense (see Figure 11).

Arrears remain largely anchored by accommodative interest rates, although we expect them to edge higher in the near term as pressures on households prevail--including modest wage growth, elevated cost of living expenses and higher prepayments for borrowers resetting from interest-only to principal and interest repayments (see Figure 12).

Although borrowers on principal and interest terms have a lower interest payment, this is generally more than compensated for through the principal repayment.

For commercial banks, while the policy developments, or lack of in the case of negative gearing and capital gains tax reform, should be supportive of an increase in volume growth, in the absence of considerably stronger volume growth, falling interest rates will continue to place pressure on margins.

There is also the broader question of risks to financial stability from increased household indebtedness (at 190% of disposable income, Australia household debt is amongst the highest in the world). For now, both the RBA and APRA appear comfortable with those risks, as falling interest rates assist with debt serviceability.

On the other hand, we believe the near term outlook is unlikely to improve for residential property developers, who have arguably endured most of the pain from tightened credit conditions over the last 18-24 months. Building approvals continue to fall (albeit, off a very high base, having increased markedly since 2012), with construction activity following suit (see Figure 13). We believe this correction has further to run.

Ready to find out how Corporate Bonds can help generate predictable income?

Get a free consultation